Joint

Agricultural and Rural Affairs Committee and

Planning and Environment

Committee

Réunion conjointe du

Comité de l’agriculture et des questions rurales et du

Comité de l’urbanisme

et de l’environnement

28 January 2009 / le 28 janvier 2009

Submitted

by/Soumis par : Nancy Schepers, Deputy City Manager/

Directrice municipale adjointe,

Infrastructure Services and

Community Sustainability/

Services d’infrastructure et

Viabilité des collectivités

Contact Person/Personne-ressource: Richard Kilstrom, Manager/

Gestionnaire, Community Planning and

Design/Aménagement et conception communautaire, Planning and Growth

Management/Urbanisme et Gestion de la croissance

(613) 580-2424 x22653,

Richard.Kilstrom@ottawa.ca

That staff be directed to circulate the proposed

amendment to the City of Ottawa Official Plan (Five-year Comprehensive Official

Plan Review) as detailed in Document 1 and the revised Infrastructure Master

Plan as detailed in Document 2, and to schedule a public meeting for March 31,

2009.

Que le personnel soit

chargé de diffuser la modification proposée au Plan officiel de la Ville

d’Ottawa (révision détaillée quinquennale du Plan officiel), telle qu’exposée

en détail dans le Document 1, et le Plan directeur de l’infrastructure révisé,

tel qu’exposé en détail dans le Document 2, et de mettre au calendrier une

réunion publique le 31 mars 2009.

In November 2008, staff presented a report that provided comprehensive information about the proposed changes to the Official Plan and Infrastructure Master Plan, including the background rationale and implications for future land-use planning. That report is available at: http://www.ottawa.ca/calendar/ottawa/citycouncil/pec/2008/11-24/agendaindex44.htm

At that time, staff indicated that in early 2009, the proposed changes to the Official Plan would be tabled to initiate the formal amendment process. That would be done in conjunction with proposed revisions to the Infrastructure Master Plan.

The purpose of this report is to:

1. Confirm the process and timeline for Council adoption of an Official Plan Amendment and approval of a revised Infrastructure Master Plan.

2. Make some updates to the proposed policies in the Official Plan based on recent input and clarifications.

3. Report on some matters that were not available in November, including:

· The revised Infrastructure Master Plan;

· The comprehensive review as a basis for an Employment Lands Strategy;

· The identification of recommended locations for the urban boundary rationalization;

· A report on the costs associated with implementation of the Official Plan and Master Plans;

· A report on the relative costs of growth in different areas of the city, in response to Motion 18/33;

· A review of the survey on intensification;

· A response to Motion 47/15 on growth management.

Public notification: This marks the beginning of the legislated Official Plan Amendment process. The proposed Official Plan Amendment and revised Infrastructure Master Plan will not be circulated in hard copy unless specifically requested. Notification will occur through:

· Newspaper advertisements in the local papers and daily papers,

· An e-newsletter to the mailing list of over 3,000 individuals and organizations,

· Updating the City’s website,

· Links to the Councillors’ websites, and

· Links to the Federation of Citizens’ Association’s website and the websites of other groups who agree to do so.

Staff will contact by letter any individual landowner affected by a proposed change in land-use designation.

Open House: As required by the Planning Act, staff will hold an open house to provide answers to questions related to the Official Plan or Infrastructure Master Plan. The Act requires one open house. Since staff have already held many such information meetings, the intent is to hold two additional ones before the end of February: one to focus on rural matters and one to focus on urban matters. Staff are also available to meet with Councillors, groups and individuals on specific matters as they arise.

Public Meeting: A public meeting before a Joint Meeting of Planning and Environment Committee and Agriculture and Rural Affairs Committee will be advertised for March 31, 2009.

Following the public meeting the Official Plan Amendment will go to City Council for adoption and then to the Minister of Municipal Affairs for approval.

The Draft Official Plan Amendment is attached as Document 1. The text is substantially the same as the document tabled and explained in November 2008. Document 1 includes a list of sections that have changed with an explanation. Those text changes since the November version are identified as “[NEW]”. A number of new Schedules are included in Document 1.

These requests have arisen in two contexts. The first includes two requests to consider lands as candidate areas for urban expansion based on a review of the agricultural attributes of the land. One is an Official Plan Amendment application by Mattamy and has not been agreed to as the LEAR score is higher than the 130-point threshold for Agricultural Resource Areas. The second is a request by Minto and has been agreed to be considered as a candidate area for urban expansion because the lands to the north are urban and to the west are General Rural and the current LEAR score is less than 130 points (see Annex 2 to Document 3).

In both of these cases the consultants argued that various aspects of the LEAR scores should be re-evaluated and in fact the methodology revisited to reflect changes in the Agricultural industry as well as changes in land use. This may very well be true and staff will initiate a study to review the LEAR approach and scores for the city as a whole. In that way, the criteria will be applied consistently across the city. This was also a request of the Agricultural Working Group who met as part of the Rural Review. Should the Minto parcel not be included as an urban expansion area, it will continue to be designated Agricultural Resource Area pending completion of the city-wide study.

There are also three requests to address the Agricultural Resource Area designation unrelated to the urban area expansion. Staff have received a request from J.L Richards (with Weston Graham Associates) relating to Part of the West half of lot 30, Concession 2, Rideau Front. This request is for the application of a General Rural Area designation in place of the Agricultural Resource Area designation. The LEAR score is below the threshold for good agricultural potential. However, parcels on three sides of the subject site are still designated Agricultural Resource Area. When the City reviews the LEAR process, it may very well be that these lands are re-evaluated and designated differently. However, for consistency, the designation should not be changed at this time.

Staff have also received a request from Novatech Engineering on behalf of the owners of the Highland Park Cemetery to redesignate the cemetery site in West Carleton from Agricultural Resource Area to General Rural Area. In addition there has been a proposal from the Upton Group to develop Agricultural Resource Area along the Rideau River north of Kars as a new “settlement area”. This would only be considered if the property was not designated Agricultural. Both of these proposals will be considered after the city-wide review of the LEAR.

Staff will initiate work on the review of the LEAR late in the spring, with input from the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food. Typically a committee of farmers, staff, agricultural experts and other representatives in the community will direct such a review. Such a committee can only focus on this work from November to February during an inactive period in farming. Therefore, a schedule will be created that responds to this requirement. Background work will begin in early summer 2009 and Committee work will be initiated by November 2009.

The Infrastructure Master Plan (Document 2) was not available in November although staff presented the main elements of the Plan. Four key changes are being proposed for the Infrastructure Master Plan (IMP):

Capacity Management Strategy: To deal with the demands of intensification and the limitations of its older infrastructure, the City has developed a Capacity Management Strategy with more detailed policy and implementation guidance than is currently available in the existing Infrastructure Master Plan policies in the following ways:

· Giving higher priority and more financial support to the assessment of system capacity;

· Giving priority to determining solutions and scheduling works for intensification and density target areas to provide both capacity for growth and to meet the needs of existing residents;

· Recommending changes through the review of development applications (e.g. to increase on-site retention of stormwater);

· Undertaking public and private capacity building projects including innovative ways to involve and work with the development community; and

· Providing additional funding for non-traditional infrastructure programs (such as water efficiency, water loss, green infrastructure and flow management) to reduce reliance on “bigger pipe” capacity building solutions.

Groundwater Management Strategy: Council adopted “The Groundwater Management Strategy” in May, 2003 and changes to the Infrastructure Master Plan policies have been proposed to reflect the direction of the adopted Strategy. The tasks proposed in the Strategy have been divided into two phases:

· For Phase 1, the City has been continuing and expanding its existing work on data collection and characterization of groundwater resources and public education.

· For Phase 2, the City will undertake the remaining tasks outlined in the strategy including: identification of contaminant sources; groundwater use assessment; trends in quality and level of groundwater; best management practices; and groundwater protection policies and legislation.

Stormwater Management Strategy: Council adopted stormwater management policies in September of 2007. These are being incorporated into the Infrastructure Master Plan. The policies were developed to provide direction to:

· City plans for stormwater management in greenfield areas;

· Retrofitting of existing areas that have been developed without stormwater management; and

· Stormwater management needs related to intensification.

Water, Wastewater and Stormwater Projects: The IMP contains a list of programs and major projects required between 2009 and 2019, and between 2020 and 2031 to support the population and employment projections and growth objectives of the Official Plan. These include: water feedermains, pump stations and reservoirs, elevated tanks and treatment plant upgrades. With respect to wastewater, the list includes wastewater collectors and treatment plant upgrades. Programs and projects that support intensification through the capacity management strategy, community-specific projects and village water and wastewater projects are separately identified. For stormwater management projects, the list includes ponds and erosion control works.

Metropolitan Knowledge International completed a comprehensive review of Employment Lands in Ottawa as part of its Phase 1 work for the Employment Lands Strategy as required by the Provincial Policy Statement. The report was provided to Planning and Environment Committee on January 27, 2009. The Phase 1 findings concluded that no additional Employment Lands are required in the Urban or Rural Area. However, it did identify two critical issues:

· Not enough employment lands are located in areas of high demand; and

· Servicing and other constraints currently limit the supply available to meet demand.

Phase 2 of the study will, among other things, identify what needs to be done to develop a strategy to address the issues identified above. It is anticipated that it could be brought to the above-noted Committee sometime in March 2009. No changes to the employment area designations are anticipated at this time.

The Residential Land Strategy indicated a requirement in the planning period for an additional 850 gross hectares of urban residential land. Staff have done a comparative review of more than 2,000 ha of primarily General Rural Area and are recommending some additional work to investigate the cumulative impact on infrastructure and to consider economies of scale. Document 3 presents that analysis and identifies the recommended actions. At this time no specific lands are being recommended for inclusion and the relative ranking of parcels will likely change as additional work is completed.

The Official Plan (OP) guides, at a high level, all land-use in Ottawa, and ultimately shapes how the City will accommodate growth and change. In many ways the Master Plans are supporting documents to the Official Plan in that they provide strategies to facilitate growth in particular locations or at particular densities. On the other hand, the Master Plans can be significant determinants of growth patterns. The ability of a light rail system to shape the way the city grows is unparalleled in recent history. The Plans therefore must be implemented in unison to achieve Council’s objectives for the future of the City. Document 4 details the financial implications and affordability of the Official Plan, Infrastructure Master Plan and Transportation Master Plan based on the 22-year term of the Official Plan. The following paragraphs summarize that document.

The Official Plan:

Implementing the Official Plan requires the City to undertake tasks and programs that may have budget pressure implications for the City. In accordance with the Planning Act, the City is also required to undertake certain on-going tasks to keep the Official Plan current. Many of these also carry budget implications for the City. The OP tasks that require funding by the City (as opposed to being funded by developers/private sector) are described in Document 4, and include the five-year reviews of the OP itself and its secondary plans, monitoring growth, preparing of Community Design Plans, implementing Design Priority Areas, and identifying and protecting Natural Heritage Systems. The cost for Natural Heritage Systems and related environmental tasks over the 22-year term is $73M, and the cost of the remaining OP tasks is $25.5M over that same term, for a total of $98.5M. A breakdown of costs to achieve these, and their funding sources, is included in Document 4.

The Infrastructure Master Plan:

The Infrastructure Master Plan (IMP) describes the major water, wastewater and stormwater capital works to service Official Plan estimates for population, households and employment to the year 2031, the term of this OP, and is estimated to cost $1.6B over that period. Over half of this cost is growth-related, and eligible for Development Charge funding. Document 4 breaks down these capital works by type, cost and funding source, and describes the details of growth-related versus rehabilitation.

The Transportation Master Plan:

The implementation of the Transportation Master Plan (TMP) will cost approximately $8.36B in new infrastructure and services over the 22-year term of the OP. Document 4 details the capital costs, operating and maintenance costs, and funding sources for rapid transit, transit priority, bus garages, transportation demand management and roads (including provisions for pedestrians and cyclists). The TMP was approved by City Council on November 26, 2008.

Development Charges as a Revenue Source:

The final section of Document 4 explains how Development Charges function, how they generally promote the principle of “growth pays for growth,” and the challenges of Development Charges as a funding source.

Council motion 18/33 was adopted on July 11, 2007 in respect of the 2007-2010 Draft City Strategic Directions report, as follows:

BE IT RESOLVED That section c under Transformation Priorities be amended by adding a new point to read as follows,

"10. Following the principles of Ottawa 20/20, ensure the review of the Official Plan includes:

a) The impact on the operating and capital budgets of development in each of these areas: inside the greenbelt; within the urban boundary outside the greenbelt; within villages; and in rural Ottawa outside of village boundaries,

b) A review of the effective measures to direct growth.”

A consultant study was commissioned to respond to part a) of the motion and the technical report, “Comparative Municipal Fiscal Impact Analysis”, Hemson Consulting Ltd., is attached as Document 5. It examines the operating and capital costs of residential development in each of the four areas compared to the associated tax revenue to the City. It should be noted that due to the complexity of the analysis, the numbers cited are more indications of the comparative situation rather than measures of absolute differences. Its conclusions are as summarized below:

1. Development inside the Greenbelt generates a surplus of revenues over costs of approximately $1,000 per additional household or $450 per capita. Figures will vary depending on whether infrastructure upgrades are required to accommodate new development;

2. In urban areas outside the Greenbelt, costs are slightly higher than revenues by approximately $70 per additional household or $25 per capita;

3. Development in villages costs more to service than the revenue it generates by approximately $500 per new household or roughly $175 per capita; and

4. In rural areas outside villages, the cost of new development exceeds revenue by approximately $160 per household or about $55 per capita.

With regard to part b) of the motion, “a review of the effective measures to direct growth” the answer is multi-faceted. The Official Plan is the main document for directing growth. For example, the proposed policies require that intensification targets be met prior to the consideration of any urban boundary expansions. City priorities for transportation and piped infrastructure improvements provide opportunities for development in some areas over others. Measures such as Development Charges can vary by area to encourage development in priority areas.

The Hemson study concluded that while there were opportunities to influence the location of residential development, it is much more difficult for a variety of reasons to influence the location of non-residential development.

Motion 47/15 was moved by Councillor Leadman and seconded by Councillor Doucet and carried by Planning and Environment Committee. It raises a number of matters mainly related to growth management within and outside of the Greenbelt. Document 6 presents the staff response to the motion. Each of the concerns raised by the Councillors is being addressed in the revised Official Plan.

BE IT RESOLVED that the following motion be referred to the consideration by Council of the Official Plan Review on 10 December 2008:

WHEREAS The City of Ottawa is reviewing its Official Plan (OP) - the central guiding document that presents a unified vision on how Ottawa will develop. Under this review, the City is committed to improve its policies by ways of the Mid-Term Governance Review, Development Charges By-Law and the Development Approval Processes;

THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED THAT City staff be directed to report to Committee and Council on methods and additional provisions in the draft Official Plan to enhance City Ontario Municipal Board (OMB) cases on zoning and development matters including but not limited to emphasis on compatibility, serviceability and community design plans;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED THAT City staff be directed to report to Committee and Council on methods and additional provisions in the draft Official Plan to meet development targets in a diffused manner across each area minimizing focus upon single site development where possible;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED THAT City staff be directed to report to Committee and Council on methods and provisions in the draft Official Plan to encourage sustainable development outside the greenbelt with focus upon building vibrant town centers and main streets with local economic development strategies;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED THAT City staff be directed to report to Committee and Council on progress on the staff led review underway on the development approval process with specific mention to:

· Encourage developers to promote architectural creativity and vibrant streetscapes and sub divisions;

· Decrease review time to improve service to the development industry;

Establish local design review committees with feedback integrated into the design review process;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED THAT City Staff be directed to report to Committee and Council on progress on this motion at the tabling of the Draft Official Plan review and be included within the scope of the Official Plan public consultation.

As part of the Official Plan review, staff organized an Intensification Forum consisting of two public sessions at Ben Franklin Place on the evenings of May 29 and June 3, 2008. Two broad topics were each addressed, one at each session:

Four different experts from across the country were invited to speak each night on these subjects in a moderated session that allowed for interaction with the audience through questions and answers.

As a follow-up, on Saturday, June 7, 2008, an Intensification Roundtable was held at City Hall that included representatives from the development community, professional architects, community associations, elected representatives’ offices, and City planning staff. The purpose of the day was for the group to identify recommended actions that could be considered to address some of the recommended actions the City, alone or in partnership with the other stakeholder groups represented, could undertake to remove barriers to achieving successful intensification. Four brief backgrounders were provided to provide some context for discussions dealing with the following general topic areas:

Each topic area had at least one representative from each of the four stakeholder groups. The sessions were professionally facilitated. In the end, the input produced by the group was synthesized into nine recommended actions. These actions were subsequently confirmed through the group. The nine recommended actions were as follows:

Action 1 – ‘Enhance Public Education to Increase Awareness/Acceptance of Intensification’

Action 2 – ‘Create a Position for a Chief Architect or Equivalent’

Action 3 – ‘Political Leadership on Design: Identify A Political Design Champion’

Action 4 – ‘Establish a formal design review board or panel to facilitate on-going effective implementation of quality design in intensification’

Action 5 – ‘Create a roundtable of various local stakeholders to facilitate exchange of information and expertise’

Action 7 – ‘Developers Initiate Early Involvement with Community on Intensification Proposals’

Action 8 – ‘Address the Relationship between Intensification, Availability of Infrastructure, and the Provision of Community Benefits’

Action 9 – ‘Review Policies to Ensure that they Work Together to Support Good Design and Intensification’

Staff is currently implementing some of these directions. In particular, it is a priority to create a corporate culture to support a more compact, mixed-use, pedestrian-oriented city.

This means good design and compatible intensification along with the infrastructure and community resources to support it. Staff are also processing an Official Plan amendment to require early consultation with the city on development proposals and to encourage early consultation with the community. An awareness program is underway that includes a video on intensification, a series of courses on planning policy and processes and user-friendly information on “understanding density”. Implementation of intensification is a focus of the City and all of these recommended directions are being explored.

In order to get a broader reaction to these recommended actions, staff placed them, along with some background context, on the City’s web site in the form of a questionnaire. The general public was asked to respond if they agreed, partly agreed, or disagreed with the recommended actions and to rank each of the actions in order of importance. People were also asked to provide reasons for their opinions and to make any additional comments they wished. Lastly, people were asked if there were any additional actions the City should consider and if any of the nine recommended actions should be deleted and why.

The public survey on the recommend actions developed from the Intensification Roundtable was posted on the City’s web site between October 20 and November 07, 2008.

The number of people providing responses to each of the nine actions ranged between 247 and 256. This amounts to well over 2000 individual comments from those who participated in the on-line survey. In the vast majority of cases, additional comment, qualification, or clarification as to why a choice of agreement, partial agreement or disagreement had been registered was provided. Virtually all responses were thoughtful opinions and there were very few ‘gratuitous’ comments. Response to the nine actions alone constituted about 134 pages of input, while an additional 14 pages or so of comments on “other actions the City should consider” were also provided. Document 7B provides a breakdown of the level of support for each of the recommended actions and an overview of the nature of the responses given. It is noted that the survey was not scientific, nor was the assessment of the replies. However, the quality of response was very high and the level of interest in the subject was quite apparent.

Finally, three submissions from individuals and one from the Federation of Citizens’ Associations of Ottawa-Carleton were made ‘off-line’.

The following Documents provide additional detail with respect to the nine recommended actions falling out of the Intensification Roundtable (and are also attached).

Document 7A – On-line Intensification Feedback Questionnaire (listing the nine recommended actions and background context)

Document 7B – Summary of the nature of responses received

Document 7C – Other Actions the City should Consider

Document 7D – Backgrounders Prepared for Intensification Roundtable

Copies of all original responses submitted to the on-line questionnaire can be provided on request. This information has not been included in this submission due to its size.

Residential Lands Strategy and Rural Settlement Strategy.

These two documents were provided in November of 2008. Since then they have been updated in minor ways and the latest versions are available as Document 8 and Document 9. The changes are identified in Documents 8a and 9a.

Public consultation on the Official Plan Review has occurred for more than a year. At this stage the Planning Act requires that the City hold one open house for the purpose of giving the public an opportunity to ask questions on the available material. Many such meetings have already been held in various parts of the city and two more are scheduled: one for the rural area and one for the urban area.

Where interested persons are of the view that their concerns have not been properly addressed in the Official Plan Amendment, those persons will have the right to appeal the amendment if they have made submissions prior to its adoption. One of the changes made with Bill 51 however is that if the amendment does not modify a particular section of the plan, there is no ability, through appealing the amendment to seek to have the portion of the Official Plan modified that Council chose not to change.

The cost of completing the Official Plan Review has been provided in Capital Account 900854. Additional costs may be incurred in 2010 to attend Ontario Municipal Board Hearings. Document 4 identifies the cost of implementing the Official Plan.

Document 1 Draft Official Plan Amendment, February, 2009

Document 2 Revised Infrastructure Master Plan, February, 2009

Figure

1 – Existing Water Distribution Schematic

Figure

2 – Existing Wastewater Distribution System Schematic

Figure 3 – Watersheds and Sub-watersheds

Figure

4 – Growth Projects 2003-2006 – Water Distribution System Schematic

Figure 5 – Growth Projects 2003-2006 –

Wastewater Collection System Schematic

Figure

6 – Growth Projects 2007-2021 – Water Distribution System Schematic

Figure 7 – Growth Projects 2003-2021 –

Wastewater Collection System Schematic

Figure

8 – Villages and Rural Servicing

Figure

9 – Private Service Enclaves

Document 3 Review of Candidate Areas for Additions to the Urban Area

Document 4 Financial Implications and Affordability of the Official Plan, Infrastructure Master Plan and Transportation Master Plan

Document 5 Comparative Municipal Fiscal Impact Analysis, Hemson Consulting Ltd

Document 6 Response to Motion 47/15 on Growth Management

Document 7 Survey on Intensification (7a, 7b, 7c and 7d also attached per page 10)

Document 8a List of Updates to Residential Lands Strategy (February, 2009)

Document 8b Revised Residential Lands Strategy (February, 2009)

Document 9a List of Updates to Rural Settlement Strategy (February, 2009)

Document 9b Rural Settlement Strategy (February, 2009)

Infrastructure Services and Community Sustainability will initiate the circulation process for a city-wide Official Plan Amendment and Schedule a Public Meeting for a Joint meeting of Agricultural and Rural Affairs Committee and Planning and Environment Committee on March 31, 2009

.

REVIEW OF CANDIDATE AREAS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE

URBAN AREA DOCUMENT 3

The Residential Land Strategy for Ottawa, 2006 to 2031,

identifies a need for some additional urban lands to the year 2031. The recommendation is for an additional 850

gross hectares of urban residential land through an urban boundary adjustment

in the updated Official Plan. The

intent of the expansion is to add small amounts of urban land to the boundary

in a number of locations and thereby use residual capacity in existing

infrastructure and provide the highest probability of integration with the

existing community. The purpose of this

summary is to present information for each candidate area and to recommend

appropriate locations for changes to the urban boundary.

The recommended expansion areas are based on balancing various

considerations:

·

The availability of land in a non agricultural designation

·

The expected absorption rate in various areas

·

The relative merit of each parcel based on a number of evaluation

criteria

|

Table 1:

Additions to the Urban Area, 1987 to 2009 |

||||

|

|

||||

Year

|

Ha added |

Gross Ha |

|

|

|

1987 |

|

31,815 |

|

|

|

1988 |

183.0 |

31,998 |

|

|

|

1988 |

26.0 |

32,024 |

|

|

|

1988 |

16.0 |

32,040 |

|

|

|

1989 |

567.9 |

32,608 |

|

|

|

1990 |

1245.0 |

33,853 |

|

|

|

1992 |

40.0 |

33,893 |

|

|

|

1994 |

2.1 |

33,895 |

|

|

|

1995 |

12.5 |

33,908 |

|

|

|

1996 |

202.0 |

34,110 |

|

|

|

2000 |

685.0 |

34,795 |

|

|

|

2001 |

- |

34,795 |

|

|

|

2006 |

470.6 |

35,265 |

|

|

|

2009 |

850.0 |

36,115 |

|

|

|

Total 1987 to

2006 |

3450.1 |

|

Increase from 1987 = 10.8% over 19 years |

|

|

Total 1987 to

2009 |

4300.0 |

|

Increase from 1987 = 13.5%% over 22 years |

|

A number of assumptions

guided the identification of candidate areas for analysis:

Secondly, the areas were

screened based on the presence of Natural Heritage System components. Focus was placed on forested areas, wet

areas, escarpments and valleylands. This

information was used to understand the availability of developable land within

the study area and to profile the possibility of securing these lands through

the process at no cost to the City.

Such natural heritage features were not included in the

definition of “gross developable” residential hectares.

Gross hectares

identified: 2039

Gross developable

hectares identified: 1561

Gross developable

residential hectares required: 850

The purpose of the

evaluation is to identify the specific 850 ha to be recommended for inclusion

in the urban area, from among the 2039 ha initially identified.

The areas that were included

as candidate areas for analysis are shown on the maps in Annex 1. The tables in Annex 1 provide a basic

description of each candidate area including the location, size, designation,

zoning, current and adjacent land uses.

Any relevant planning history is also provided.

The lands selected as

candidate areas were not influenced by ownership or by the submission of

planning applications. However, three

landowners submitted studies to indicate that the Agricultural Resource Area

designation on their land was inappropriate.

Annex 2 is the staff response to these studies. Otherwise, the existing designations were

taken at face value and not reviewed.

Annex 3 is a list of

submissions received during the review process. While this material was scrutinized, it was not the basis for

identifying candidate areas.

The objective is to identify

an additional 850 hectares of gross residential land. Gross residential land includes residential land, public streets

and a limited range of non-residential uses typically found in a neighbourhood

such as parks, schools, community centres, churches, convenience level retail

and stormwater facilities. It is

usually measured in dwelling units per land area. It does not usually include significant natural areas that would

be ‘in addition to’ the gross residential requirements.

The candidate areas have been examined with respect to the presence of

natural heritage features. The land

described as natural heritage is subtracted from the parcel size and the

remainder is the gross residential area of the candidate parcel.

As stated earlier, the overall objective is to select areas that make

the best use of existing available infrastructure capacity and community

resources. These parcels should be

developable within a reasonable period of time such as the in the next 5 to 10

years. The Official Plan is reviewed

every five years and the condition of City infrastructure is monitored

continuously. Lands that score lower

today may very well be good candidates later.

It is very clear that each of the candidate sites could be made to

work. This is very much an exercise of

the relative merits of the various candidate areas.

Each candidate area has been evaluated against the criteria in Table

2. All distances are measured from the

closest point in the candidate area to the facility. The possible scores are distributed as follows:

·

Servicing: 12

·

Transportation: 12

·

Community Facilities: 12

·

Potential conflicting land uses:

6

·

Physical Characteristics: 4

·

Demand for land: 3

·

Total Potential Score: 49

Table 2 –

Evaluation Criteria and Scores

|

Criteria |

Description |

Scores |

Highest Possible Score |

|

1. Depth to

bedrock |

·

Presence of bedrock near surface |

· 0 – overburden

<2 metres · 1 – overburden

>2 and <5 metres · 2 – overburden

greater than 5 metres |

2 |

|

2. Environment –

soil constraints |

·

Presence of potential soil constraints |

·

0 – present ·

2 – absent |

2 |

|

3. Servicability –

Water |

·

Pressure zone capacity, pumping requirements, topography, access to

infrastructure, ability to provide looping |

· 0 – major

expenditure required to service ·

1 – significant expenditure required ·

2 – moderate expenditure required

· 3 – minor

expenditure required · 4 – no

expenditure required |

4 |

|

4. Servicability –

Wastewater |

·

Residual capacity in the downstream trunk, local servicing ease,

proximity of expansion area to downstream collector system, pumping

requirements |

· 0 – major expenditure

required to service ·

1 – significant expenditure required ·

2 – moderate expenditure

required

· 3 – minor

expenditure required · 4 – no

expenditure required |

4 |

|

5. Servicability -

Stormwater |

·

Presence or absence of subwatershed plan, floodplain constraints, requirements

for stormwater management facilities |

·

0 – significant storm-water issues identified ·

2 – medium stormwater issues ·

4 – minor or no stormwater issues |

4 |

|

6. Accessibility

–Arterial Roads |

·

Direct access to an existing or planned arterial road |

·

0 – No direct access ·

2 – Direct access to one arterial road ·

4 – direct access to two or more |

4 |

|

7. Accessibility -

Transit |

·

Distance to existing or planned rapid transit network or to park and

ride |

·

1 – more than 3.5 km ·

2 – between 2.1 and 3.5 km ·

3 – between 1.1 km and 2.0 km ·

4 – less than 1.0 km |

4 |

|

8. Connectivity

with Community |

·

Road connectivity to adjacent parcels and communities |

·

0 – Poor – obstructions in 2 or more directions ·

2 – Medium – unable to

connect in one direction

·

4 – Good – connections exist or can be planned |

4 |

|

9. Accessibility

to existing or planned retail/commercial focus |

·

Distance to Mainstreet or Mixed Use Centre |

·

1 – driving distance 3 km or more ·

2 – cycling distance 1 to 3 km ·

3 – walking distance less than 1 km |

3 |

|

10. Ability to work

in community |

·

Jobs/Housing Balance. This is

cumulative, starting at the parcel nearest to the urban boundary |

·

1 – insufficient number of jobs for balance ·

2 – slightly below jobs/housing balance ·

3 – meets or improves jobs/housing balance |

3 |

|

11. Accessibility

to community facilities |

·

Distance to Major Recreational Facility |

·

1 – Far; more than 5 km ·

2 – Medium; 2.5 to 4.9 ·

3 – Close; less than 2.5 km |

3 |

|

12. Availability of

emergency services |

·

Average distance to emergency fire and police (total /2) |

·

1 – Far; more than 8 km ·

2 – Medium; 5 to 7.9 km ·

3 – Close; less than 5 km |

3 |

|

13. Conflicting

Land Uses |

·

Agricultural Resource Area within 500 metres |

·

0 – yes ·

2 – no |

2 |

|

14. Conflicting

Land Uses |

·

Aggregate Resources within 500metres or Landfill within 500metres

(former or existing) |

·

0 – yes ·

2 – no |

2 |

|

15. Conflicting

Land Uses |

·

Adjacent rural development:

Country Lot or Village Development |

·

0 – yes ·

2 – no |

2 |

|

16. Land Absorption |

·

Area has fewer than 20 years supply of urban land |

·

0 – South ·

3 – West or East |

3 |

|

Total |

|

|

49 |

Various ways exist to

distribute the 850 hectares of additional urban land. In total size it is equivalent to an area 50% larger than the

designated urban area of Leitrim or to an area about half the size of the total

urban area of Stittsville.

1. Council could

place it all in one location to facilitate comprehensive planning of the

lands. This is not recommended because

such a strategy will have the greatest impact on the demand for services. It is intended that this addition be more of

a rationalization of the urban boundary and not the creation of a new

community. This particular work is

looking for the location that makes the most efficient use of existing

infrastructure and services.

2. Council could

distribute it based on the existing absorption rate in each urban centre of

Kanata/Stittsville, South Nepean, Riverside South, Leitrim and Orleans. This approach treats the Nepean South market

as completely distinct from the Riverside South market. Table 3 summarizes the land consumption

patterns over the last 10 years and the implications for land supply if the

850 hectares will contribute to providing a similar number of years supply

in each area.

Table 3– Potential

Distribution of 850 Ha Based on Historical Absorption Rates in Urban Centres

|

Area |

10-year

demand (average per year) Net

Hectares1 |

Total

Supply of Vacant Land (net

ha 2007) |

Approximate

years supply (end

of 2007) |

Proposed

Additional Gross Residential Hectares |

Approximate

years supply with additions (end

2007)2 |

|

|

Kanata/Stittsville |

48.0 |

880.7 |

18.3 |

315 |

21.6 |

|

|

South Nepean |

34.9 |

501.3 |

14.4 |

1703 |

16.8 |

|

|

Riverside South |

9.6 |

552.7 |

57.5 |

0 |

57.5 |

|

|

Leitrim |

6.3 |

138.3 |

22.0 |

0 |

22.0 |

|

|

Orléans |

30.7 |

477.1 |

15.5 |

365 |

21.5 |

|

|

Total |

126.5 |

2,550.1 |

20.2 |

850 ha |

23.5 |

|

|

* Notes: 1. Total does not add

because Leitrim average is based only on the 5-year period 2003-07 during

which there was building activity. 2. Gross ha are converted to net ha based on an

assumption of 50%. 3. Only 170 ha have been identified as candidate areas in

South Nepean so this is the maximum total that can be added. |

|||||

3. Council could

distribute the 850 hectares based on growth patterns in three urban centres in

the west, south and east. This treats

the South Nepean, Leitrim, Riverside South market as a block. Over the next 20 to 25 years it is highly likely

that the rate of growth in Riverside South will increase in response to the

construction of rapid transit as well as the Strandherd-Armstrong Bridge. Such

an approach is described in Table 4.

Table 4 – Potential Distribution of 850 Ha based on Historical

Absorption Rates in Generalized Urban Locations

|

Area |

10-year demand

(average per year) Net Hectares |

Total Supply of

Vacant Land (net ha 2007) |

Approximate

years supply (in 2007) |

Proposed

Additional Gross Residential Hectares |

Approximate

years supply with additions (end 2007) |

|

West |

48.0 |

880.7 |

18.3 |

425 |

22.8 |

|

South |

47.7 |

1,192.3 |

25.0 |

0 |

25.0 |

|

East |

30.7 |

477.1 |

15.5 |

425 |

22.4 |

|

Total |

126.5 |

2,550.1 |

20.2 |

850 ha |

23.5 |

4. Council could

distribute the 850 ha equally among the three urban areas east, west, and

south. This is shown in Table 5. It does not recognize the historical trends

in each area.

Table 5 – Potential

Distribution of 850 Ha based on an equal share to Generalized Urban Locations

|

Area |

10-year demand

(average per year) Net Hectares |

Total Supply of

Vacant Land (net ha 2007) |

Approximate

years supply (in 2007) |

Proposed

Additional Gross Residential Hectares |

Approximate

years supply with additions (end 2007) |

|

West |

48.0 |

880.7 |

18.3 |

283.3 |

21.3 |

|

South |

47.7 |

1,192.3 |

25.0 |

283.3 |

28.0 |

|

East |

30.7 |

477.1 |

15.5 |

283.3 |

20.1 |

|

Total |

126.5 |

2,550.1 |

20.2 |

850 ha |

23.5 |

Annex 1 includes a profile

of each area and a summary table of all evaluations. Such an analysis results in the following distribution of

additional urban land (Table 6).

Table 6– Potential Distribution of 850 Ha Based on Comparison of all

candidate areas based on criteria

|

Area |

10-year demand

(average per year) Net Hectares |

Total Supply of

Vacant Land (net ha 2007) |

Approximate

years supply (in 2007) |

Proposed

Additional Gross Residential Hectares |

Approximate

years supply with additions (end 2007) |

|

West |

48.0 |

880.7 |

18.3 |

405.2 |

22.5 |

|

South |

47.7 |

1,192.3 |

25.0 |

168.6 |

26.8 |

|

East |

30.7 |

477.1 |

15.5 |

313.4 |

20.6 |

|

Total |

126.5 |

2,550.1 |

20.2 |

887.2 |

23.7 |

Conclusions

1.

This is the preliminary phase of analysis and has not yet concluded on

the appropriate parcels for inclusion in the urban area. The analysis in this report examines over

2,000 hectares of land in 38 parcels.

2.

This is a relative evaluation that provides scores for infrastructure,

transportation, community facilities, physical characteristics, and absorption

trends. It is likely that any of these

parcels could be engineered to work but some are less expensive than others.

3.

The intent is to add small amounts of urban land to the boundary in a

number of locations and thereby use the residual capacity in existing

infrastructure and provide the highest probability of integration with the

existing community. However, it is

apparent that there is not a lot of residual capacity in the City’s

infrastructure. Therefore, in most

cases, improvements are required. Some

of the higher scoring areas actually failed in their servicing score.

4.

This analysis does not look clearly at the cumulative effect of adding

adjacent parcels. In some cases, the

addition of one parcel could be accommodated in the existing

infrastructure. However, in other cases

improvements are required. If that is

the case, does it make sense to add only one parcel or should the city be

looking at economies of scale and more strategic investments? Additional work is required in this regard.

5.

The summary tables indicate where components of the Natural Heritage

System exist. As the land is urbanized,

it is the intention to preserve these areas as natural areas in the urban

fabric. However, work is required to

more accurately map these areas and this work requires access to the

properties.

6.

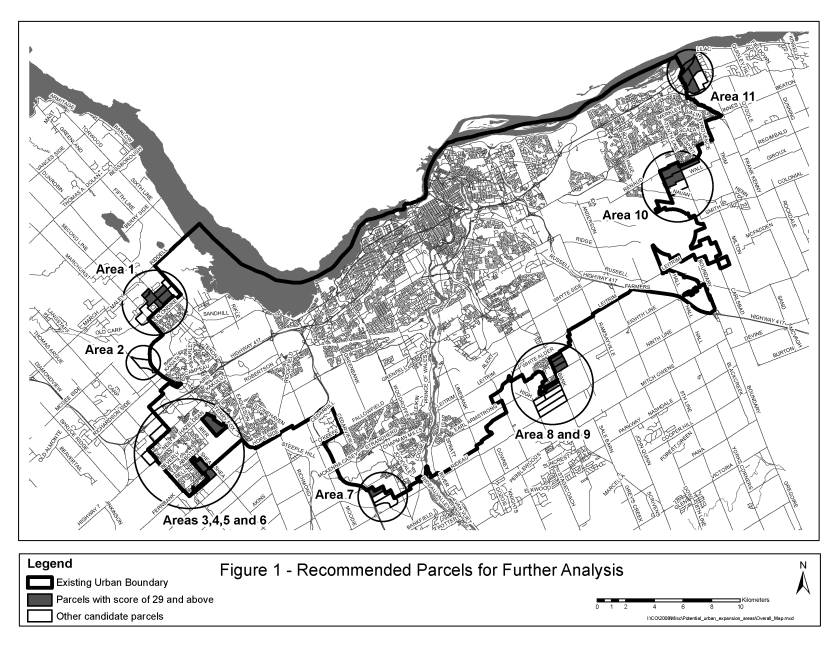

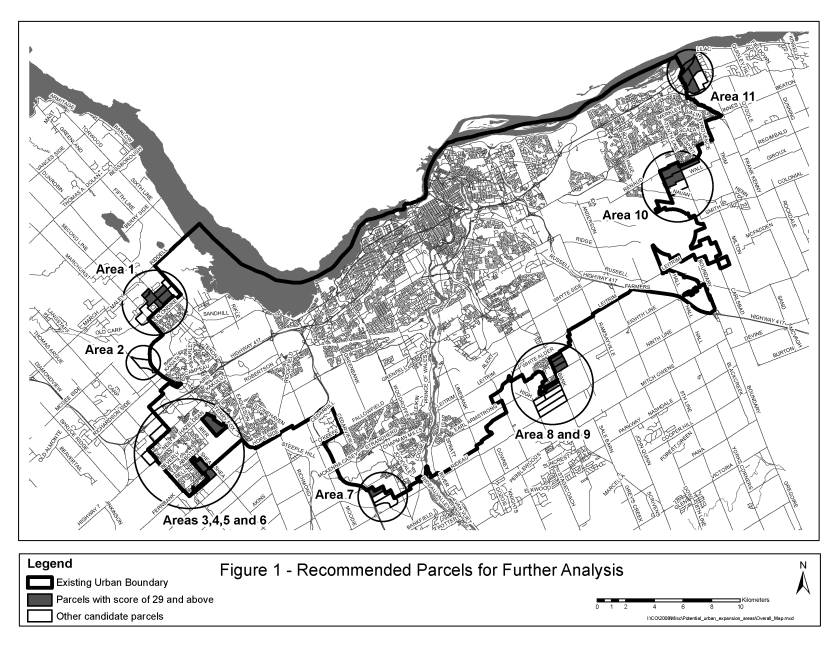

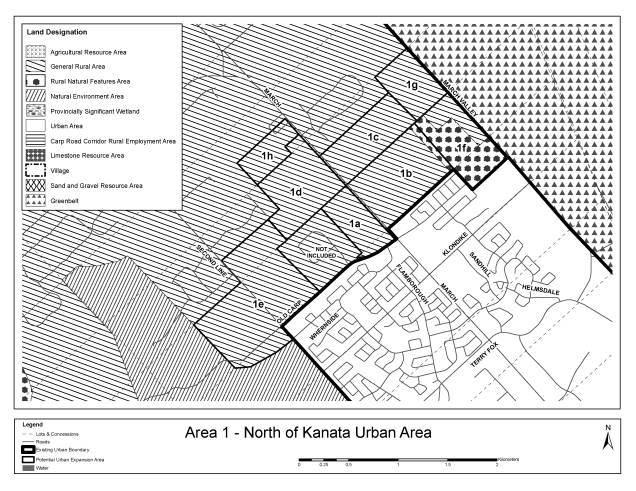

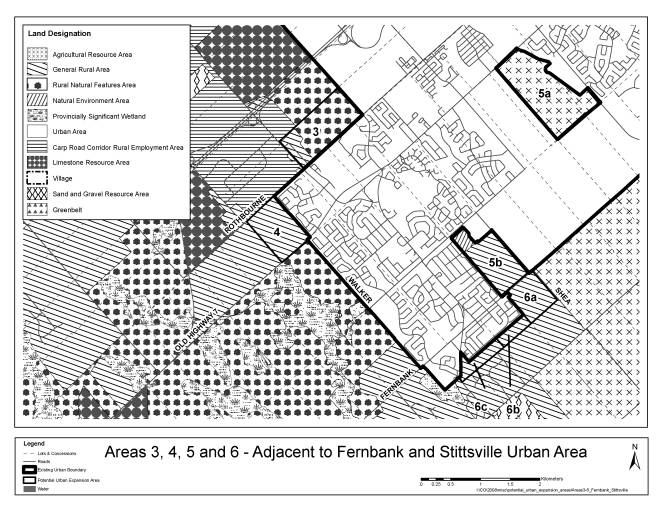

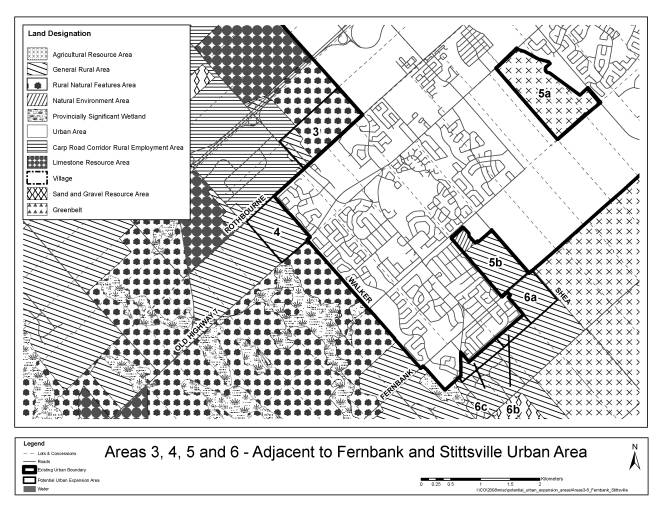

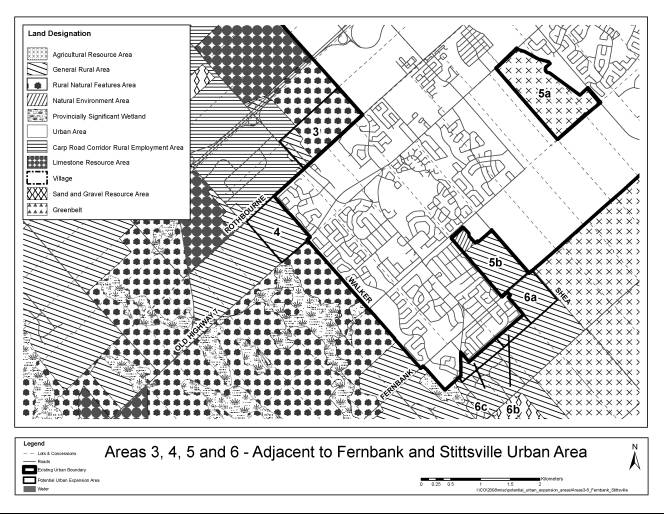

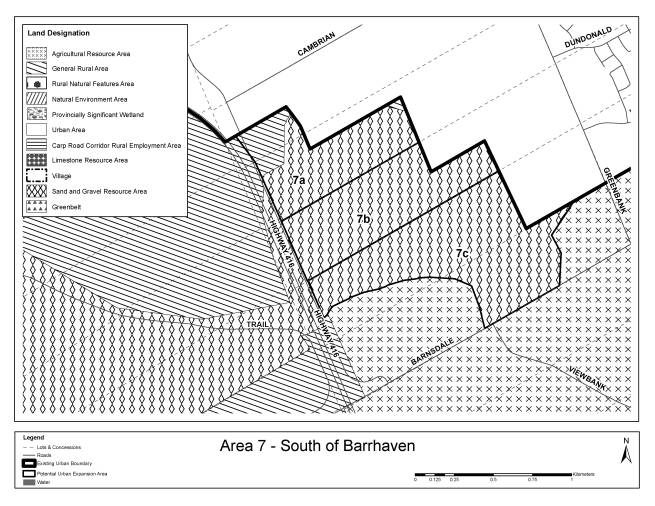

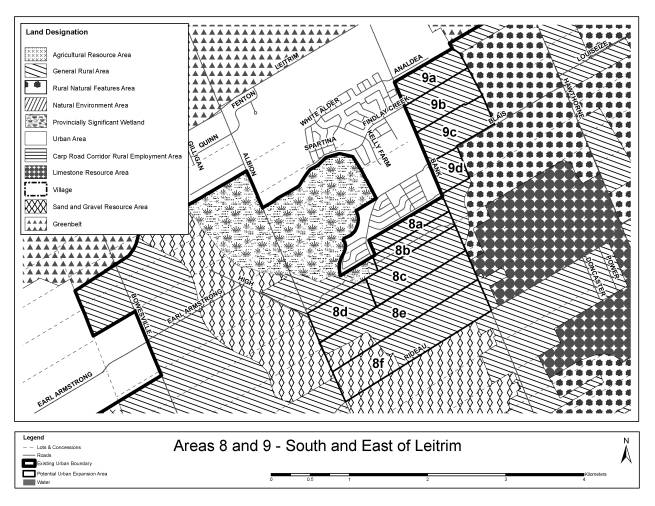

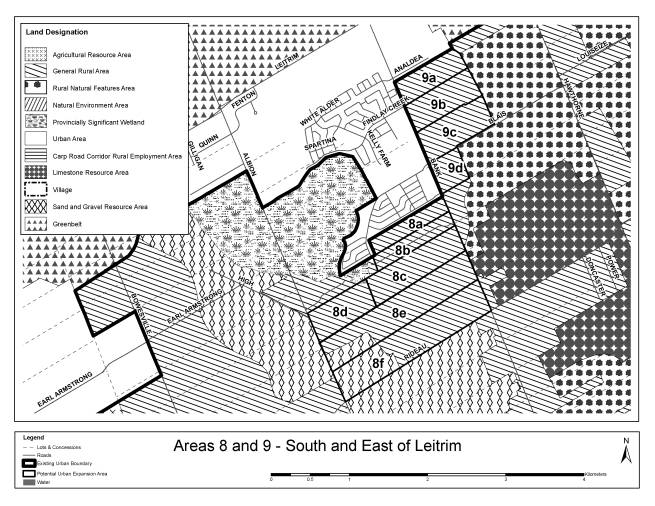

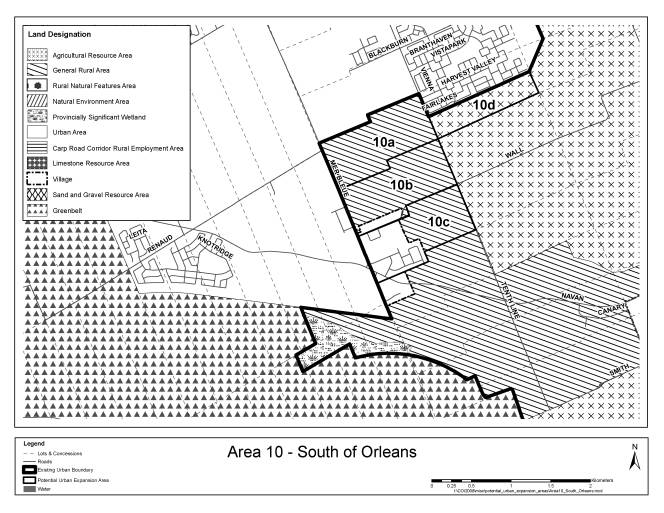

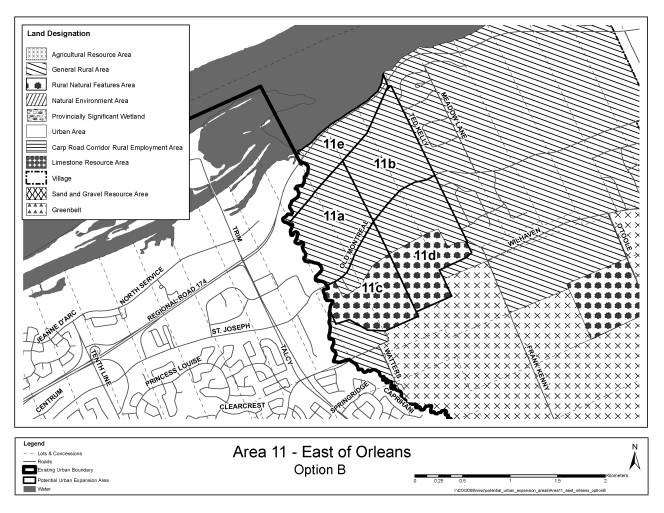

Figure 1 shows the areas achieving the highest points in the

preliminary. These include:

a.

Areas 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, 1h north of Kanata

b.

(Areas 5a and 5b – no additional analysis required)

c.

Areas 6a, 6b and 6c south of Stittsville

d.

Area 7a south of South Nepean

e.

Areas 8a, 9a, 9b, 9c adjacent to Leitrim

f.

Areas 10a, 10b and 10d south of Orleans

g.

Areas 11a, 11b, 11c, 11e east of Orleans.

7.

Figure 1 should not be read as a list of recommended areas, since the

Phase 2 analysis may change the ranking significantly.

Recommendations

1.

The City will undertake some additional servicing analysis over the

next month to examine the serviceability of the preferred parcels. In particular, the analysis will review all

of the servicing studies submitted to date in addition to considering the

cumulative effect of urban land additions and economies of scale. This will provide a basis for revisions to

the decision rules, the scoring criteria and actual scores for the

infrastructure component of the analysis if appropriate.

2.

At least two weeks prior to the public meeting on March 31, staff will

provide an Official Plan Schedule indicating the recommended locations for

urban expansion based on the revisions made through the servicing analysis.

3.

The recommendations made at that time will also indicate what servicing

issues need to be addressed prior to development occurring on these parcels.

4.

City staff will arrange to get more accurate mapping of Natural

Heritage Features. The report prepared

for March 31 public meeting will indicate how these lands are to be secured by

the City.

5.

Areas 5a and 5b were included in the analysis for the Fernbank

community design plan and their servicing has been incorporated into the master

servicing study for Fernbank.

Therefore, no additional analysis is required for these two parcels.

Annex 1 –

Evaluation of Candidate Areas

|

Location Northern extension of the Kanata urban area on either side of March

Road. Part of Lot 12, Concessions II,

II and IV, March |

OP Designation: General Rural Area. |

Current Land Use(s): Primarily farms and forested areas. Some pockets of rural development within the study

area. The Ottawa Central Rail Road

line runs north-south through the eastern portion of parcels b and c while

Shirley’s Brook runs north-south through the western portion of b and c. |

|

Size: Gross ha = 349 Gross developable ha = 303 |

Zoning: RU – Rural Countryside |

|

|

Planning Status Part of 1e is within an OPA application from Richcraft Group of

Companies. |

Adjacent Land-Use designations: North:

General Rural

East: Greenbelt Rural South: General Urban Area West: Natural Environment

Area |

Adjacent Land Use(s): to the south is Urban Kanata, primarily

residential uses. To the west are the

South March Highlands. To the north

is more countryside. To the east is

the Greenbelt. Three existing areas

of rural development are located within or adjacent to the study area. |

Natural Heritage System

General Comment

|

The area is bounded by the South March

Highlands (Natural Environment Area) on the west and the Greenbelt on the

East. While there are some small

vestiges of forested land, most of the area is old fields and hedgerows. No obvious soil problems are evident.

|

||||

Area Comments

|

Gross Ha

|

Natural Heritage System Feature

|

NHS Removed

|

Other Constraints

|

Gross Developable Ha

|

1a

|

24.4

|

|

|

1.0 ha floodplain

|

23.4

|

1b

|

56.7

|

|

|

2.0 ha floodplain |

54.7

|

1c

|

38.7

|

|

|

2.0 ha floodplain |

36.7

|

1d

|

46.2

|

|

|

|

46.2

|

1e

|

95.6

|

Woodland

|

27.0

|

|

68.6

|

1f

|

42.1

|

Woodland

|

5.0

|

3.0 ha floodplain

|

34.1

|

1g

|

26.6

|

|

|

3.0 ha floodplain

|

23.6

|

1h

|

18.2

|

|

|

Removed church and cemetery 2.6 ha

|

15.6

|

Total

|

348.6

|

|

27.0

|

13.6

|

302.9

|

Servicability

|

Servicability – water |

The water supply to this area is good. The land above elevation 90m,

which is most of the area west of March Rd., needs to be serviced through the

existing Morgan’s Grant Pump Station to maintain satisfactory pressures. This

requires upgrades to the pump station and suction pipes. |

|

Servicability – wastewater |

Two trunk sewers service this area. Only the East March Trunk (near

Terry Fox east of March Rd.) has any residual capacity. This residual would

service about 1900 units. Upgrades could provide for up to 3400 units. The

second trunk (Hines Rd. sewer) may require upgrades in the future to

accommodate growth in the Village of Carp and represents an opportunity for the

future for capacity creation for additional development. |

|

Servicability – stormwater and natural hazards |

Shirley’s Brook subwatershed plan would require updating to guide

development. Some floodplain constraints exist in parcels east of March Road.

Parcels west of March Road may have areas where overburden is shallow

(blasting may be required to service). No significant drainage constraints

exist that could not be overcome with application of conventional engineering

methods. |

Accessibility

Area

|

Access to Arterial Roads

|

Distance to Future Rapid

Transit (km)

|

1a

|

March Road

|

0

|

1b

|

March Road |

0

|

1c

|

March Road |

0.6

|

1d

|

March Road |

0.74

|

1e

|

None

|

1.0

|

1f

|

None

|

0.9

|

1g

|

None

|

1.5

|

1h

|

March Road

|

1.5

|

Area

|

Connectivity

|

Distance to

Mainstreet or MUC (approx km)

|

Jobs/Housing

Balance

|

1a

|

Medium

– from March Rd but not to community in south

|

7

|

Improved

|

1b

|

Medium

– from March Rd but not to community in south

|

7

|

Improved

|

1c

|

Medium

– rural subdivision to the north

|

8

|

Improved

|

1d

|

Medium

– partly blocked in south (country lots) and in west (country lots)

|

8

|

Improved

|

1e

|

Poor

– NEA to west, country lots to east and north. But connects to Old Carp Road and Second Line Road

|

8

|

Improved

|

1f

|

Poor

– Rail on west and greenbelt on east and rural natural feature to south

|

8

|

Improved

|

1g

|

Poor

– Rail on west and greenbelt on east and rural natural feature to south

|

9

|

Improved

|

1h

|

Medium

– good connection to South could be accomplished but Church and cemetery

barriers on the east

|

8.8

|

Improved

|

Integration with Community (cont’d)

Area

|

Distance to

Facilities (km)

|

||

Proposed Kanata

North Recreation Centre (Innovation Drive)

|

Kanata Leisure

Centre and wave Pool

|

J Mlacak Centre

and Art Gallery

|

|

1a

|

2.1

|

7.1

|

6.5

|

1b

|

2.2

|

7.2

|

6.6

|

1c

|

2.8

|

7.8

|

7.2

|

1d

|

2.8

|

7.8

|

7.2

|

1e

|

3.1

|

8.1

|

7.5

|

1f

|

3.1

|

8.1

|

7.5

|

1g

|

3.7

|

8.7

|

8.1

|

1h

|

3.6

|

8.6

|

8.0

|

Integration with Community (cont’d)

Area

|

Distance to

Facilities (km)

|

|||

Old March Town

Hall

|

Library

|

Police

|

Fire Station 45

|

|

1a

|

0.4

|

6.5

|

8.3

|

2.1

|

1b

|

0.5

|

6.6

|

8.4

|

2.1

|

1c

|

1.1

|

7.2

|

9.0

|

1.7

|

1d

|

1.1

|

7.2

|

9.0

|

1.4

|

1e

|

1.4

|

7.5

|

9.3

|

2.8

|

1f

|

1.4

|

7.5

|

9.3

|

3.0

|

1g

|

2.0

|

8.1

|

9.9

|

2.6

|

1h

|

1.9

|

8.0

|

9.8

|

0.5

|

Potential Conflicting Land Uses

Area

|

Ha Agricultural

Resource Area within 500 metres

|

Ha Aggregate

Resources within 500 metres

|

Ha Landfills

within 500 metres

|

Country Lot and

Village Development

|

1a

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

Marchbrook Circle

|

1b

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

None

|

1c

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

Hedge Drive

|

1d

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

Marchbrook Circle and Nadia

|

1e

|

0

|

0

|

2.6 (former Kanata-1)

|

Marchbrook Circle and Thomas Fuller

|

1f

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

None

|

1g

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

Hedge Drive

|

1h

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

Wildacre

|

Depth to Bedrock

Area

|

Depth of

Overburden

(metres) |

1a

|

2 to 3

|

1b

|

2 to 3

|

1c

|

2 to 3

|

1d

|

2 to 3

|

1e

|

2 to 3

|

1f

|

2 to 3

|

1g

|

2 to 3

|

|

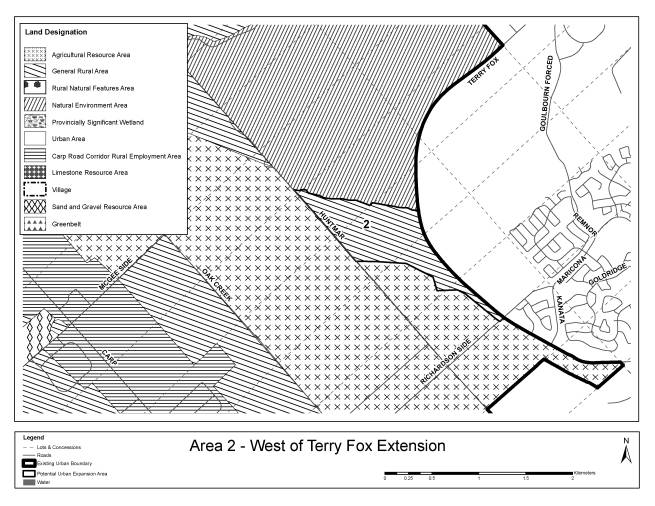

Location West of the alignment of the future Terry Fox Drive extension |

OP Designation: General Rural Area |

Current Land Use(s): Undeveloped scrub land |

|

Size: Gross ha = 79 Gross developable ha = 51 |

Zoning: RU – Rural Countryside |

|

|

Planning Status Richcraft Group of Companies has submitted an Official Plan Amendment

Application that includes these lands. |

Adjacent Land-Use designations: South and West: Agricultural

Resource Area East: Urban Area North: Natural Environment

Area. |

Adjacent Land Use(s): Huntmar Drive to the west, Carp River to

the South, future Terry Fox alignment to the east and South March Highlands

to the north. |

Natural Heritage System

General Comment

|

Bounded on the north by an NEA (South March

Highlands) and Agricultural to the south.

Bounded by Carp River to the south

No organic soils or indicators of Leda Clay

|

||||

Area Comments

|

Gross Ha

|

Natural Heritage System

Feature

|

NHS Removed

|

Other Constraints

|

Gross Developable Ha

|

2

|

79.0

|

Escarpment

|

1.0

|

27.0 ha Carp River floodplain |

51.0

|

Servicability

|

Servicability – water |

Service from extension (if possible ) of Broughton water. |

|

Servicability – wastewater |

There is no single nearby local sanitary sewer with spare capacity.

The nearest trunk sewer is the Kanata Lakes Trunk, some 4 km away. |

|

Servicability – stormwater and natural hazards |

There would be a need to update the impact assessment for the Carp

River. The lands are generally flat and have poor drainage. Stormwater

management may be challenging because of the mild slopes and outlet

constraints. |

Accessibility

Area

|

Access to

Arterial Roads

|

Distance to

Town Centre Rapid Transit (km)

|

2

|

Would have access to a future extension of

Terry Fox Drive

|

4.1

|

Area

|

Connectivity

|

Distance to

Mainstreet or MUC (approx km)

|

Jobs/Housing

Balance

|

2

|

Medium

–Connectivity to future Terry Fox Drive and Huntmar Road. No other development on that side of road.

|

4.0

|

improved

|

Integration with Community (cont’d)

Area

|

Distance to

Facilities (km)

|

||

Proposed Kanata

North Recreation Centre (Innovation Drive)

|

Kanata Leisure

Centre and Wave Pool

|

J Mlacak Centre

and Art Gallery

|

|

2

|

3.5

|

5.6

|

6

|

Integration with Community (cont’d)

Area

|

Distance to

Facilities (km)

|

|||

Old March Town

Hall

|

Library

|

Police

|

Fire Station

Teron Road

|

|

2

|

n.a.

|

6

|

4.3 (new station)

|

4.3

|

Potential Conflicting Land Uses

Area

|

Ha Agricultural

Resource Area within 500 metres

|

Ha Aggregate

Resources within 500metres

|

Ha Landfills

within 500 metres

|

Country Lot and

Village Development

|

2

|

117

|

0

|

0

|

none

|

Depth to Bedrock

Area

|

Depth of

Overburden (metres)

|

2

|

2 to 3

|

|

Location: North of Stittsville urban boundary, west of Kanata West urban

boundary, south of Hwy 417 and three lots east of Carp Road |

OP Designation: Rural Natural Feature |

Current Land Use(s): Vacant Forest |

|

Size: Gross ha = 79 Gross developable ha = 79 |

Zoning: RU – Rural Countryside |

|

|

Planning Status: -no active application -subject of an appeal on the 2003 Official Plan urban boundary |

Adjacent Land-Use designations: South and East: Urban West: Carp Road North: Rural Natural Feature |

Adjacent Land Use(s): -Vacant to North -Residential in South -Planned employment in East -Residential along Carp Rd in west |

Natural Heritage System

General Comment

|

The parcel is designated as rural natural feature. Vegetation has been cleared from the

property, therefore, there are no natural heritage system features. |

||||

Area Comments

|

Gross Ha

|

Natural Heritage System

Feature

|

NHS Removed

|

Other Constraints

|

Gross Developable Ha

|

3

|

79.0

|

|

0

|

0

|

79.0

|

Servicability

|

Servicability – water |

The watermain on Carp Rd. could service a portion of this area near

Carp Rd. The remaining land needs to be in a different pressure zone and

would best be serviced through future Kanata West and existing Stittsville

watermains. |

|

Servicability – wastewater |

There are no sewers in the vicinity with excess capacity. The

Stittsville Trunk sewer could have residual capacity but it is about 4 km

south of this site. The preferred solution would be to provide capacity in

the Kanata West sewer system. |

|

Servicability – stormwater and natural hazards |

Drains to Feedmill Creek (within Carp River watershed). Existing

studies would require updating; some areas of shallow overburden (blasting

may be required to service). |

Accessibility

Area

|

Access to Arterial Roads

|

Distance to Future Rapid

Transit (km)

|

3

|

Direct Access to Carp Road

|

4.3

|

Area

|

Connectivity

|

Distance to

Mainstreet or MUC (approx km)

|

Jobs/Housing

Balance

|

3

|

Poor

– closed portion of Rothbourne Road allowance, limitations on crossings of

Feedmill Creek and existing Lloydalex Cr. limit access

|

1.7

|

improved

|

Area

|

Distance to

Facilities (km)

|

||

Goulbourn

Recreation Complex

|

Walter Baker

Park and Kanata Rec Centre and Theatre

|

Stittsville

Community Centre

|

|

3

|

4.0

|

5.6

|

2.7

|

Area

|

Distance to

Facilities (km)

|

||

Library

|

Police

|

Fire Station 81

|

|

3

|

4.0

|

7.4

|

4.0

|

Area

|

Ha Agricultural

Resource Area within 500 metres

|

Ha Aggregate

Resources within 500metres

|

Ha Landfills

within 500 metres

|

Country Lot and

Village Development

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

Rural street within block

|

Depth to Bedrock

Area

|

Depth of

Overburden

(metres) |

3

|

2 to 3

|

|

Location West of Stittsville, north of Hazeldean Road |

OP Designation: General Rural Area |

Current Land Use(s): Fields, forest, one residential use |

|

Size: Gross ha = 59 Gross developable ha = 45 |

Zoning: RU – Rural Countryside |

|

|

Planning Status No application |

Adjacent Land-Use designations: North: Carp Road West: General Rural South: Rural Natural Feature

East: Urban Area. |

Adjacent Land Use(s): Residential to the east, forested to the south, forest and farm to

west and mineral resource to the north. |

Natural Heritage System

General Comment

|

The land parcel is situated at the

northwestern edge of Stittsville, south of Rothbourne Road. The land parcel is adjacent to the

Goulbourn Wetland Complex. The land

contains 14 ha of woodlands.

|

||||

Area Comments

|

Gross Ha

|

Natural Heritage System

Feature

|

NHS Removed

|

Other Constraints

|

Gross Developable Ha

|

4

|

59.0

|

Woodland

|

17.0

|

2.3 (hydro r-o-w)

|

39.7

|

Servicability

|

Servicability – water |

This is part of future Stittsville Pressure Zone. Some pipe extension

will be required from the existing water pipe on Hazeldean Rd. and the future

Stittsville pump Station will require pump upgrades. |

|

Servicability – wastewater |

There are no sewers in the vicinity with excess capacity. The

Stittsville Trunk sewer could have residual capacity but it is about 3.5 km

south of this site. Flow monitoring of the existing sewer system might

provide some opportunities to use existing infrastructure for a portion of

this site. The Master Servicing for Kanata West can be reviewed there is an

opportunity to consider a pump

station and forcemain to access future sewers in Kanata West. |

|

Servicability – stormwater and natural hazards |

Drains to Feedmill Creek (within Carp River watershed). Drainage of

Area 4 may be challenging because of constraints created by the existing

Timbermere subdivision to the east. Existing studies would require updating;

some areas of shallow overburden (blasting may be required to service). |

Accessibility

Area

|

Access to Arterial Roads

|

Distance to Future Rapid

Transit (km)

|

4

|

Direct Access to Hazeldean Rd

|

4.4

|

Area

|

Connectivity

|

Distance to

Mainstreet or MUC (approx km)

|

Jobs/Housing

Balance

|

4

|

Poor

- Not well connected to existing development

|

1.5

|

improved

|

Area

|

Distance to

Facilities (km)

|

||

Goulbourn

Recreation Complex

|

Walter Baker

Park and Kanata Rec Centre and Theatre

|

Stittsville

Community Centre

|

|

4

|

3.9

|

5.4

|

3.0

|

Area

|

Distance to

Facilities (km)

|

||

Stittsville

Library

|

Police

|

Fire Station 81

|

|

4

|

4.3

|

7.3

|

4.3

|

Area

|

Ha Agricultural

Resource Area within 500 metres

|

Ha Aggregate

Resources within 500 metres

|

Ha Landfills

within 500 metres

|

Country Lot and

Village Development

|

4

|

0

|

9.0

|

0

|

None adjacent

|

Depth to Bedrock

Area

|

Depth of

Overburden

(metres) |

4

|

2 to 3

|

|

Location Two parcels within the study area of the Fernbank Estates community

design plan. |

OP Designation: Agricultural Resource Area and General Rural Area |

Current Land Use(s): 5a is farmed 5b is partially tree covered |

|

Size: Gross ha = 183 Gross developable ha = 163 |

Zoning: AG – Agricultural RU – Rural Countryside |

|

|

Planning Status Has been included in the Fernbank community design plan. Part of 5a is the subject of an OPA application from Richcraft Group

of Companies |

Adjacent Land-Use designations: Urban Area and Future Urban Area.

5b also has General Rural Area to the south. |

Adjacent Land Use(s): 5a is surrounded by Fernbank Future Urban Area and 5b is adjacent to

Fernbank in the west, the Sacred Heart High School and Goulbourn Recreation

Complex in the north, Stittsville Urban Area in the east and rural

undeveloped land to the south. |

Natural Heritage System

General Comment

|

5a and 5b are situated adjacent to Fernbank

lands already included inside the urban boundary. 5a abuts the Carp River, whereas 5b is located southwest of

Sacred Heart High School. 5b is 10%

organic soils

|

||||

Area Comments

|

Gross Ha

|

Natural Heritage System

Feature

|

NHS Removed

|

Other Constraints

|

Gross Developable Ha

|

5a

|

114.2

|

|

|

9 ha

floodplain

|

105.2

|

5b

|

68.7

|

Woodland

|

10.0

|

1 ha (hydro r-o-w)

|

57.7

|

Total

|

182.9

|

|

10.0

|

|

162.9

|

Servicability

|

Servicability – water |

This area is included in the Fernbank CDP and servicing could be

easily integrated with future development. |

|

Servicability – wastewater |

This area is included in the Fernbank CDP and servicing could be

easily integrated with future development. Upgrades to the Hazeldean Pump

Station will be needed before these areas can proceed. These upgrades will

also be required for full development of Fernbank. |

|

Servicability – stormwater and natural hazards |

Area 5a is in the Carp River watershed area 5b is part of the Jock

River watershed. Drainage of these lands has been considered in the Fernbank

CDP EMP, which is nearing completion. Drainage / stormwater management of the

alternative sites is reasonably straightforward using conventional

engineering methods. |

Accessibility

Area

|

Access to Arterial Roads

|

Distance to Future Rapid

Transit (km)

|

5a

|

Direct access to Hazeldean Road

|

0

|

5b

|

Direct Access to Fernbank

|

2.2

|

Area

|

Connectivity

|

Distance to

Mainstreet or MUC (approx km)

|

Jobs/Housing

Balance

|

5a

|

Medium

connectivity- hydro corridor and trans Canada trail intersect. Carp River borders part of site

|

0 – Hazeldean Rd.

|

Improved

|

5b

|

Medium

connectivity -Trans Canada trail

|

0.6 Stittsville Mainstreet

|

Improved

|

Area

|

Distance to

Facilities (km)

|

||

Goulbourn

Recreation Complex

|

Walter Baker

Park and Kanata Rec Centre and Theatre

|

Stittsville

Community Centre

|

|

5a

|

2.2

|

0.7

|

4.1

|

5b

|

0.1

|

4.8

|

1.2

|

Area

|

Distance to

Facilities (km)

|

||

Library

|

Police

|

Fire Station 81

|

|

5a

|

2.2 (Hazeldean Library)

|

3.0

|

2.0 (#41)

|

5b

|

1.28

|

5.6

|

1.28

|

Area

|

Ha Agricultural

Resource Area within 500 metres

|

Ha Aggregate

Resources within 500 metres

|

Ha Landfills

within 500 metres

|

Country Lot and

Village Development

|

5a

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

None

|

5b

|

13

|

0

|

0

|

none

|

Depth to Bedrock

Area

|

Depth of

Overburden

(metres) |

5a

|

5 to 10

|

5b

|

0 to 2

|

|

Location South of Stittsville Urban Area and south of area 5b |

OP Designation: General Rural Area |

Current Land Use(s): 6c is cleared for development and the rest is scrub and old fields. |

|

Size: Gross ha = 72 Gross developable ha = 66 |

Zoning: RU – Rural Countryside |

|

|

Planning Status Ray Bell has an active Country Lot Subdivision application on Area 6c

and has an active application for an urban expansion |

Adjacent Land-Use designations: North: Urban Area and Future

Urban Area East: Agricultural Resource

Area South: Agriculture Resource

Area and General Rural Area West: General Rural Area |

Adjacent Land Use(s): South of 6c is a Country Lot Subdivision, Stittsville residential is

to the north and Agriculture is to the east. |

Natural Heritage System

General Comment

|

Located southwest of the urban boundary in

Stittsville, these parcels are situated amongst residential development, idle

and active agriculture.

|

||||

Area Comments

|

Gross Ha

|

Natural Heritage System

Feature

|

NHS Removed

|

Other Constraints

|

Gross Developable Ha

|

6a

|

39.6

|

|

|

6.0 (hydro r-o-w)

|

33.6

|

6b

|

12.3

|

|

|

|

12.3

|

6c

|

19.8

|

|

|

|

19.8

|

Total

|

71.7

|

|

|

6.0

|

65.7

|